I plan tomorrow to write the follow-up to Friday's post on punk rock careerism. In the meantime, I give you another installment of Art Class.

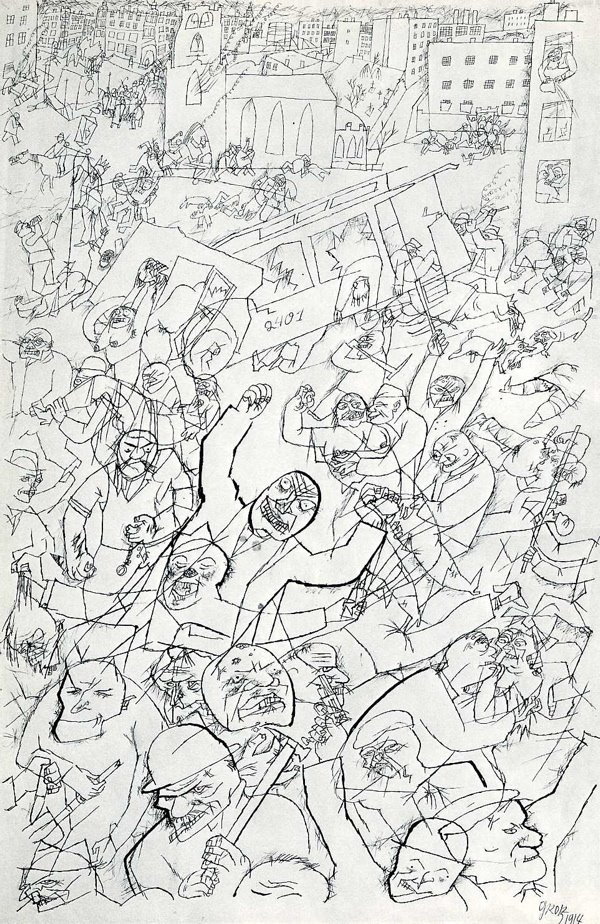

This week's bitter laughter image, entitled "Suicide," comes from George Grosz (1893-1959).

Like last Otto Dix, the subject of the last Art Class installment, Grosz was a participant in the First World War, an experience that was to leave a lasting mark upon his art. After the war, Grosz joined the German Communist Party (KPD), but left a year later after visitng Russia, where he met both Trotsky and Lenin.

The 1920s saw Grosz's art work destroyed (like Dix) after he allegedly insulted the German army. In order to escape the rule of the Nazis, Grosz left Germany in 1932, settling in New York, where he stayed until the final days of his life. He became a naturalized citizen in the 1950s, and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1954.

Grosz's art resembles Dix's in its content. Largely Grosz is remembered as a satirist ofWeimar Germany and his unflinching look at its people. His early work has all the formal bravado of Dada, but what makes him perhaps distinctive from the diverse array of talented modernists working Berlin in the 1920s is that his work seems at times prescient of the imminent comeuppance of another art form--the cartoon. The way in which Grosz deploys the charicature, however, prevents most viewers from assimilating his human forms to that medium, largely because the backgrounds of these paintings contextualize the people in them in such a way that the flatness of the people is not immediately legible.

The cityscape is also a prominent feature in "Republican Automatons," (right) where all the human figures are overly rounded, blank mannequins. Their thoughts are fed to them, and their actions prompted by the gears at the lower right, suggesting the utter emptiness of a seemingly meaningful gesture--the waving of the flag. The city scape is again a conspicuous feature, suggesting that somehow the city is to blame for the citizenry's inability to self-actuate.

The cityscape is also a prominent feature in "Republican Automatons," (right) where all the human figures are overly rounded, blank mannequins. Their thoughts are fed to them, and their actions prompted by the gears at the lower right, suggesting the utter emptiness of a seemingly meaningful gesture--the waving of the flag. The city scape is again a conspicuous feature, suggesting that somehow the city is to blame for the citizenry's inability to self-actuate.

Other of Grosz's pieces that resonate with me are his drawings. Here the cartoonishness of his work really comes out, and the bleakness of the black and white brings home the utter absurdity of inter-war Germany, to say nothing of inter-war Europe as a whole. Late in life, Grosz was to depict the Nazi era (cf. his Hitler painting, "Cain, or Hitler in Hell"), but by far his most successful work was his efforts to depict all aspects of Weimar society--soldier, socialists, prostitutes, military doctors, aristocrats, etc.

Late in life, Grosz was to depict the Nazi era (cf. his Hitler painting, "Cain, or Hitler in Hell"), but by far his most successful work was his efforts to depict all aspects of Weimar society--soldier, socialists, prostitutes, military doctors, aristocrats, etc.

Galleries of his work can be found here, here and here.

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Art Class - George Grosz

Posted by

Tim

at

1:56 PM

![]()

Labels: comics, George Grosz, painting, prosthesis, WWI

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment