Harper's Weekly brings my attention to this very important piece of literary news: after decades of neglect, Kafka's porn collection is seeing the light of day.

Harper's Weekly brings my attention to this very important piece of literary news: after decades of neglect, Kafka's porn collection is seeing the light of day.

A stash of explicit pornography to which Franz Kafka subscribed has emerged for the first time after being studiously ignored by scholars anxious to preserve the iconic writer's saintly image.

Having stumbled by chance across copies in the British Library in London and the Bodleian in Oxford while doing unrelated research, James Hawes, the academic and Kafka expert, reveals some of this erotic material in Excavating Kafka, to be published this month. His book seeks to explode important myths surrounding the literary icon, a "quasi-saintly" image which hardly fits with the dark and shocking pictures contained in these banned journals.

Their additional significance is that the publisher, Dr Franz Blei, was also the man who first published Kafka in 1908 - a series of miniature stories later gathered in his book Meditation.

Hawes, an Oxford graduate and university lecturer, emphasises his total admiration for the literary Kafkaesque genius who wrote brooding classics such as The Metamorphosis, The Castle and The Trial, and argues that these discoveries merely show Kafka as more human than the popular image. He believes that "suppressing" them detracts from sensible assessment of his work, and has even led to nonsensical evaluation.

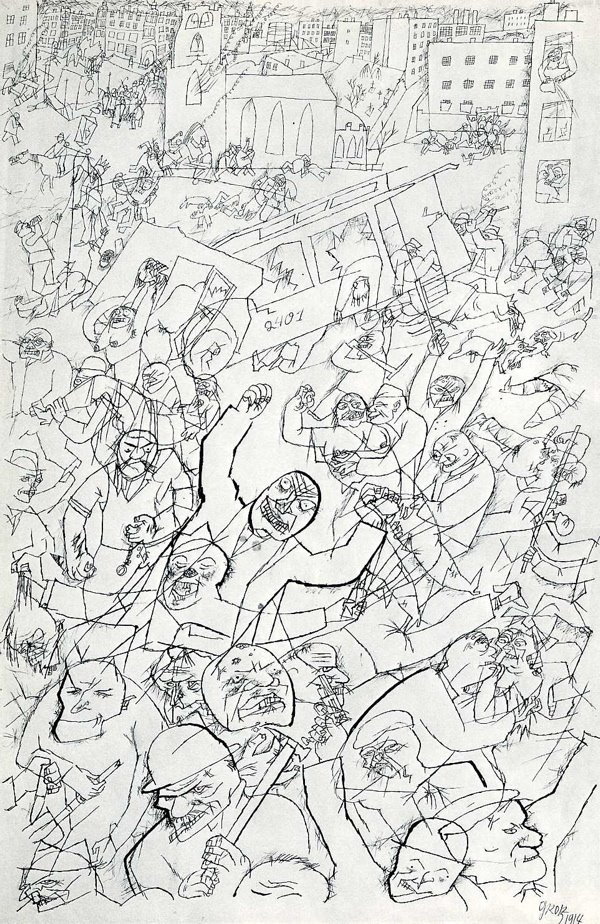

Even today, the pornography would be "on the top shelf", Dr Hawes said, noting that his American publisher did not want him to publish it at first. "These are not naughty postcards from the beach. They are undoubtedly porn, pure and simple. Some of it is quite dark, with animals committing fellatio and girl-on-girl action... It's quite unpleasant."

Now, there are several things funny about this. First, consider the fact that Kafka's stash of dirty magazines has apparently been housed at Cambridge and Oxford for years. Second, consider the fact that Hawes feels his Kafka expertise qualifies him to deem the collection "top shelf." His authority, you understand, is vast.

But on a more serious note, I have to look down at this kind of literary scholarship. Porn? Really? In my most generous academic posture, I could maybe imagine some kind of scholarship coming out of this that shows the influence of pornography and modernist spectacle on Kafka's work. Similar work has been done on the topic of Kafka and his passion Jewish theater, so there's no reason why the topic of pornography couldn't be equally illuminating. But if this article is any indication of how this archive will be used, we can assume that it will contribute to an evolving biography that casts Kafka less and less in the role of idyllic mystic.

Of course, we hardly need Kafka's centerfolds to make this biography. Kafka is one of the writers about whom book upon book is written, it seems, because the fiction is so good and yet resistant to the kind of exegetical proliferation that we find in other modernist texts. What results is a fetishization of Kafka--and, here, a fetishization of his fetishes.

The case against Kafka's saintliness seems to gather steam every few years. Fingers are pointed at Max Brod, whose editorial efforts (which saved Kafka from oblivion) seem to stack the chips in favor of a mystical Kafka. Yet, we hardly need to look under Kafka's matress in order to rewrite the story Brod wrote. Indeed, if anything, the idea that Brod proferred such a saintly figure is somewhat absurd, recent polemics aside. Brod famously argued that The Castle is an allegory about divine grace, and that The Trial is an allegory of divine justice. Kafka's first English translators, Edwin and Willa Muir, helped spread this version of Kafka by how they framed their translations between 1930 and 1938. However, by the end of WWII, theological readings of Kafka ceased to hold sway. Here's Muir on Kafka as a theologian:

- In his 1930 preface to The Castle, Muir argued that The Castle and The Trial are best defined as “metaphysical or theological novels.” Muir recommended that readers think of The Castle “as a sort of modern Pilgrim’s Progress … [as] a religious allegory.” Muir reasserts this in various forms in both 1933 and 1934.

- By his 1938 introduction to America, Muir seems less concerned with religion than he does with Kafka’s depiction of “the human situation.”

- Four years after the conclusion of the war, he completely revised his earlier reading of Kafka, arguing that The Castle and The Trial “are not allegories. The truths they bring out are surprising or startling, not conventional and expected, as the truths of allegory tend to be. They are more like serious fantasies.”

1 comment:

best waterproof mattress protector uk

Post a Comment